(National Funeral Museum)

When Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson died below the deck of the HMS Victory in 1805, he was already a legend of his time. Celebrated as a hero of the Napoleonic Wars and world-famous for his victories on the Nile, Cape St Vincent and now Trafalgar, when word reached England’s shores of the musket ball that took his life, the Nation threw itself into giving him perhaps the greatest funeral the country had ever seen.

(Royal Collection)

Although Nelson’s voyage home was anything but grand, famously placed in a barrel of spirits lashed to the mainmast, his final journey would see him carried by several illustrious ships – a fitting tribute to the most famous figure in Britain’s Naval history.

First, the Victory would take him to the Thames Estuary, then the Yacht Chatham, owned by the Esteemed Sir George Grey, took him to his lying in state at Greenwich. Charles II’s prestigious 35-foot-long State Barge would take Nelson down the Thames to Whitehall in a grand procession, escorted by sixty other State, Admiralty and City of London.

But amongst this distinguished list of famous names, a new craft was built just for the occasion – perhaps the most spectacular of them all.

(Royal Museums Greenwich)

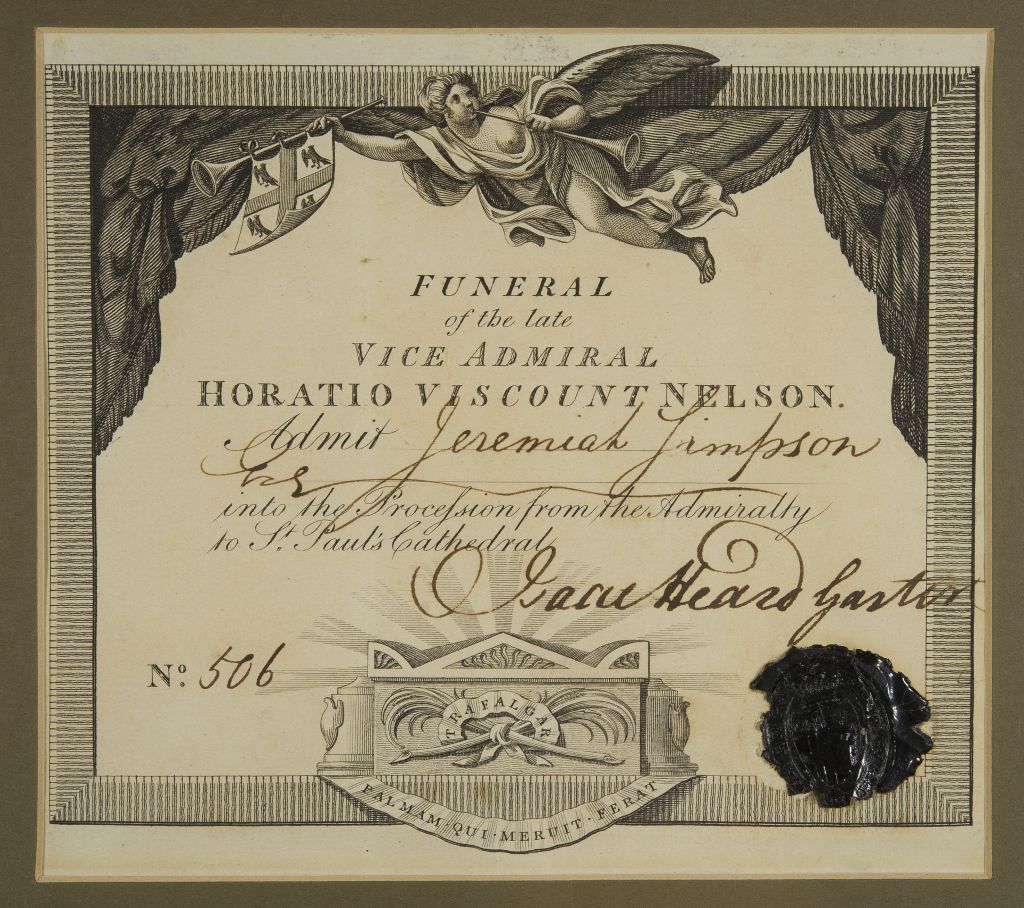

In the just over eleven weeks between Nelson’s death and burial, two institutions forged half a hundred plans to oversee the funeral. The first was the College of Arms, the historic institution traditionally charged with organising State funerals, and second was the Admiralty, desperate to both honour their most famous son and reassure the public on their continuing Naval might.

Of course, they needed a funeral car – the Navy’s poster boy couldn’t travel on a hand-drawn bier like some country farmer. The challenge was how to balance the traditional ‘heraldic’ pomp of previous State funerals, like Sir Philip Sidney and the Duke of Marlborough, with the new century’s spirit of funerary spectacle – as well as capturing the growing myth behind Nelson himself.

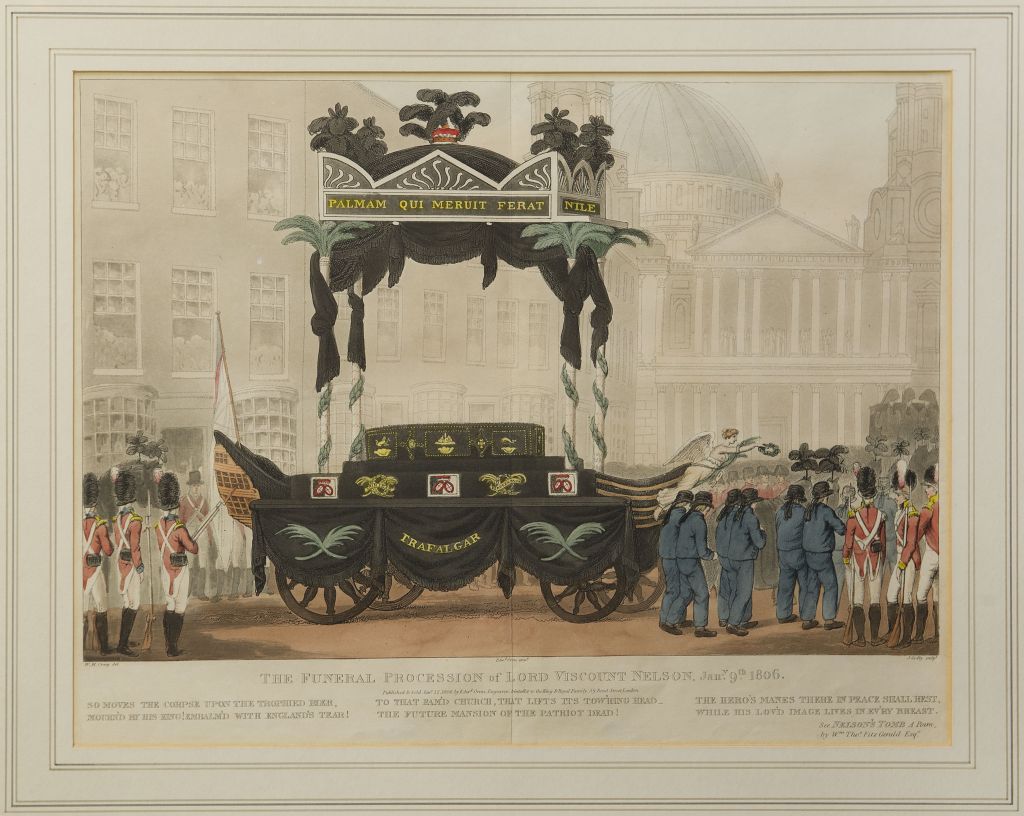

What was decided was nothing short of genius. Nelson would not simply ride to St Paul’s by horse and hearse; instead, he would sail, proud and vibrant, through the capital’s streets in the flagship where he took his last breath.

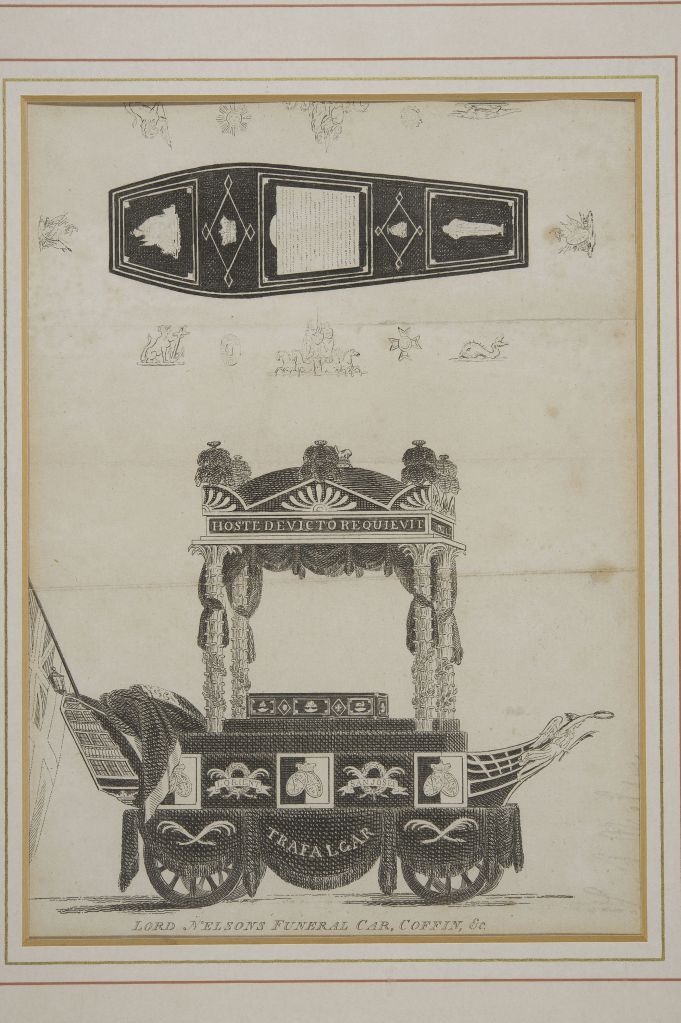

The car itself was a work of art. Designed to imitate the Victory’s bow and stern, it was led by a miniature version of the ship’s figurehead and hung with the white Naval ensign, while Nelson’s coffin rested on the raised “quarterdeck”. Over the top stood a black velvet canopy supported by four pillars carved to look like palm trees, topped with luxurious black ostrich feathers. The sides were hung with six painted hatchments each bearing Nelson’s coat of arms.

(National Funeral Museum)

In case the message wasn’t clear enough, the sides were emblazoned not only with the names of Nelson’s two ‘greatest’ battles, “NILE” and “TRAFALGAR”, but also Nelson’s personal Latin motto, translated as “let he who has earned it bear the palm”, and the words “hoste devicto requievit”, meaning “he conquered and went to rest”.

Painted in bright colours and pulled by six black horses, the car was a marvel – combining traditional heraldic arms with a striking, theatrical twist, it was a tribute to Nelson that immortalised both his victories and the Victory in one enormous, 18-foot spectacle.

But who created it? Who was responsible for designing this triumph of funerary art? This seems to be a fiddly issue, but amongst several sources two candidates stand out.

The first is familiar to most students of the Regency – one Mr Rudolph Ackermann. Born in Saxony, he was most famous as a publisher and printmaker, known for producing a beautiful series on the monuments of Westminster Abbey as well as several satirical works such as Dr Syntax and The English Dance of Death.

On the day following Nelson’s funeral, Ackermann produced a print of the car that was published by J Page to an eager public. However, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, one of Ackermann’s contemporaries, passingly mentions in his memoirs that he “believes” Ackermann “designed the whole thing”. Because of the print and this testimony, many historians, including Ackermann’s Biographer John Ford, firmly state that the printmaker was commissioned to design the car by the government in 1805.

(British Library)

However, Page’s print also gives credit to a second, less familiar name. Abbe Ange Denis “McQuin”, or MacQuin, was a French ecclesiastical scholar who fled the French Revolution in 1792. Settling in Hastings, he made a living from his former pastime as an artist before coming to work for the Royal College of Arms as a sign painter and draughtsman. A close friend of Sir Isaac Heard, who was the Garter King of Arms and the chief organiser of Nelson’s funeral, the car is attributed to McQuin not only by Page’s print but also by the 1806 Naval Chronicle and his obituary in the 1823 Gentleman’s Magazine, as well as an article produced by the College’s modern day journal Coat of Arms in 1989.

Naval Historian Nicholas Tracy finds a middle ground, suggesting that Ackermann in fact “commissioned” MacQuin to design the car for him. However, this does seem like an odd jump considering MacQuin’s extensive pre-existing connections with Heard and the College. Perhaps, considering their collaboration on the print and Ackermann’s own background in coachbuilding back in Saxony, the printmaker could have consulted with the College on the car’s base and frame while MacQuin handled the heraldic and the more theatrical elements. Alas, this question goes beyond our interests here – a subject for another day.

(National Funeral Museum)

This leaves us with who was actually brought the majestic piece to life.

As a State Funeral, it was the Royal Undertakers France and Banting who ‘undertook’ the task of furnishing Nelsons funeral, famously building his coffin and dressing St Paul’s Cathedral. However, it seems the job of building the car itself was allotted to the Royal Upholders, Messrs Elliott of New Bond Street. Referenced by several articles in The Times, Messrs Elliott are credited with both the car and the canopy over the Cathedral’s catafalque, while a “Mr Elliott” consulted on a few different prints of the car in the days and weeks following the funeral.

Most importantly, the National Archives holds extensive records on the funeral’s expenses, including charges made by an “Elliott” towards a “Funeral Car, Hearse & Mourning Coaches”. For the car and all its furnishings, including a Viscount’s funeral coronet, Messrs Elliott charged £486 3s, around £21,400 in today’s money, not including charges made for ostrich plumes, the horses and other amenities. Newspapers put the car’s final figure somewhere close to £700 – a whopping £30,851 today.

(National Archives LC 2/38/2 folio 8v)

Though they had just over two months to design, approve and construct the magnificent set piece, you can imagine the car was no mean feat to build. Probably put together like contemporary theatre sets with paste and board, you can’t help but think of the number of unnamed hands who carved the stern, painted the signs and came home covered in stray, black ostrich fluff.

So, by the evening of January 8th, the stage was set for Messrs Elliot to deliver the car to the Admiralty, where it would wait overnight for a few last-minute changes to be made the following morning. Originally there were supposed to be four Royal Navy Lieutenants sitting on each corner of the car, but this was discarded. The pall and coronet were also moved out of sight, the latter travelling inside one of the mourning coaches. This was all to ensure that everyone would get a better view of the coffin – the “quarterdeck” was also raised for the same reason.

The procession eventually left Whitehall for St Paul’s at around 10:30, riding along specially cleaned and gravelled streets for the occasion. Nelson’s coffin was escorted by 32 Admirals, over 100 Captains and around 100,000 soldiers, with about 20,000 volunteers lining the pavements. The whole parade took about three and a half hours to pass the estimated 20,000 -30,000 spectators, crammed onto balconies or crushed together on the street, and the papers report that the car truly was the star of the show – according to the Morning Post “no one saw it pass without the tribute of a grateful and melancholy tear”.

The company finally arrived at St Paul’s at around Two O’Clock, and the coffin was received by twelve Sea Men from the Victory at the Great Entrance. After just a short time in the spotlight, the car’s job was done.

So what happened next?

Once the service was over, Messrs Elliott had the car taken just down the road to the King’s Mews, where it stayed on display to the public for three days. Then, on January 13th, Sir Isaac Heard had the car moved to the Painted Hall at Greenwich, where it remained for twenty years as a long-term memorial – standing not far from the same place that Nelson lay in state.

(Royal Museums Greenwich)

However, in 1826, after years of neglect and decay, the car was finally dismantled, with most of its parts discarded, lost or sold.

Only two significant parts of the car appear to have survived to the present day. The biggest and perhaps the best piece is the carved and painted figurehead. This is held by Royal Museums Greenwich and is on display at the National Maritime Museum as part of their “Nelson, Navy, Nation” exhibition. Meanwhile, another relic went up for sale at Sotheby’s in December 2020 – one of the six silk hatchments that hung on the side of the car. This was estimated to value around £30,000-£50,000.

Apart from that, we only have fragments – a few tin letters, scraps of velvet and casts of small decorative ornaments – all hidden amongst the vast RMG collection. The rest of the car in all it’s finery is lost to history.

(Royal Museums Greenwich)

But, thankfully for us, the car’s image lived on, bolstered by the burgeoning consumerism of Georgian Britain. The image captured in Ackermann’s and hundreds of other London engraver’s prints was reproduced in hundreds more commemorative mementoes; from ceramic jugs to glass mezzotints – even children’s toys.

(Royal Museums Greenwich)

The car’s iconic silhouette became an enduring image of the funeral and the man it came to commemorate. People from across the country’s counties and classes were eager to have some part of the Vice Admiral to hold on to, and the car was accepted as one of many icons in the growing arsenal of means to mourn.

So, while only a small puzzle piece in the near-mythic life and death of Vice Admiral Nelson, the car remains an icon of funerary history. It was the centre of a complex mechanism of ritual and power that embodied tradition, but it also appealed to the pits – cloaked in all the bells and whistles of a heraldic State Funeral, it also played with the popular appeal of model ships, naval flags and ostrich plumes.

Together, the car captured its country’s contemporary appetite for public spectacle, all whilst striking a chord with key iconography and perhaps even the very real emotions at the heart of the whole event – how the death of one of Britain’s most famous figures, struck down at the height of his ‘greatest’ victory in the middle of an ongoing war, left both the Navy and it’s country metaphorically ‘at sea’.

Nelson sailed in many ships to many places, won many battles and left behind many tales to tell. But in those few hours, travelling just under two and a half miles from Whitehall to St Paul’s, he was carried by what was, for one shining moment, the most famous ship in Britain’s fleet.

By Minette Butler – Curator

If you have any inquiries about our museum – please email us at nfm@tcribb.co.uk.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Museum Collections

Royal Museums Greenwich, Set of toy bricks (2022) <https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-211115> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Royal Museums Greenwich, A polychrome full-length figurehead of the mythical Greek messenger Nike (goddess of Victory) from the front of Nelson’s funeral car. (2022) <https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-18799> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Newspapers

Chester Chronicle, Feb 14 1806, p. 4.

Hampshire Chronicle, Jan 20, p. 1.

Morning Chronicle, Jan 3 1806, p. 4.

Morning Post, Jan 8 1806, p. 3.

Morning Post, Jan 9 1806, p. 3.

Morning Post, Jan 13 1806, p. 3.

The Times, Jan 4 1806, p. 2.

The Times, Jan 10 1806, p. 2.

Other

Anon., The Naval Chronicle for 1806: Containing a General and Biographical History of The Royal Navy of the United Kingdom; with a Variety of Original Papers on Nautical Subjects: Under the Guidance of Several Literary and Professional Men: Volume The Fifteenth(Shoe Lane: Joyce Gold, 1806), p. 233 in Internet Archive, <https://archive.org/details/navalchronicleco15londiala/page/n5/mode/2up> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Fairburn, J., Fairburn’s (2nd) edition of the Funeral of Admiral Lord Nelson(Wallbrook: John Fairburn, 1806), p. 100 in Google Books, <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Fairburn_s_2nd_edition_of_the_funeral_of/XzwIAAAAQAAJ?hl=en> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Haydon, B. R., The Autobiography and Memoirs of Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786-1846), ed. by Tom Taylor, 2nd edn (New York: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1926), p. 31.

Nichols, J., The Gentleman’s Magazine Vol 93 Part 2 (Westminster: E Cave, 1823), p. 180- 182 in Google Books, <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Gentleman_s_Magazine/WstDAQAAMAAJ?hl=en> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Nichols, J., The Gentleman’s Magazine Vol 1 (London: W. Pickering, 1834), p. 180- 182 in Google Books, <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Gentleman_s_Magazine/n1BIAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1> [accessed 22 December 2022].

The British Museum, Elliott (2022) <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG207853> [accessed 20 December 2022].

The National Archives, Nelson, Trafalgar and Those Who Served: Details of the costs of Nelson’s funeral – LC 2/38/2 folio 8v (2022) <https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/nelson/gallery8/popup/costs.htm> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Prints

The British Museum, An exact representation of the grand funeral car (2022) <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1871-0812-5288> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Secondary Sources

Adams, B., London Illustrated (UK: The Library Association, 1983), p. 228.

Beard, G. and Gilbert, C., Dictionary of English Furniture Makers 1660-1840 (Leeds: WS Maney & Son, 1986), in British History Online, <https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/dict-english-furniture-makers/e> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Curl, J., The Victorian Celebration of Death (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2001), p. 210-211.

Ford, J., Ackermann, The Business of Art 1783-1983 (London: Ackerman, 1983), p. 31 in Google Books, <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Ackermann_1783_1983/9CNKAQAAIAAJ?hl=en> [accessed 20 December 2022].

France, T., ‘Nelson’s Funeral Director’, The Nelson Dispatch, 14.1, (2021), 39-42.

Heard, S., Sir Isaac Heard: The man who helped the nation mourn Nelson (2019) <https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/library-archive/sir-isaac-heard-man-who-helped-nation-mourn-nelson> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Jenks, T., ‘Contesting the Hero: The Funeral of Admiral Lord Nelson’, Journal of British Studies, 39.4, (2000), 422-453 (p. 438).

Parsons, R., ‘The Herald Painter’, Coat of Arms, Summer.146, (1989), in <https://www.theheraldrysociety.com/articles/the-herald-painter/> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Royal Museums Greenwich, The Death of Nelson (2022) <https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/what-were-nelsons-last-words> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Royal Museums Greenwich, The Painted Hall Greenwich, from the Upper Hall, showing Nelson’s funeral car (2022) <https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-108085> [accessed 20 December 2022].

The History Press, Vice Admiral Lord Nelson’s state funeral (2022) <https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/vice-admiral-lord-nelson-s-state-funeral/> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Sothebys, A fine painted silk hatchment from the State Funeral Carriage of Vice-Admiral Viscount Nelson, 1805 (2020) <https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2020/treasures-2/a-fine-painted-silk-hatchment-from-the-state> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Tracy, N., Britannia’s Palette: The Arts of Naval Victory (Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), p. 168 in Google Books, <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Britannia_s_Palette/FqQuI_8T4esC?hl=en> [accessed 20 December 2022].

Wheeler, H. and Broadley, A., Napoleon and the Invasion of England; the Story of the Great Terror Vol II(London: J Lane, 1908), p. 273 in Internet Archive, <https://archive.org/details/napoleoninvasion02wheeuoft/page/172/mode/2up?q=nelson%27s+funeral+car> [accessed 20 December 2022].

One response to “Sailing Beyond: Nelson’s Funeral Car ”

Excellent and knowledgeable. Learnt a lot about Nelson and his death and funeral.

LikeLike