When you picture a “body snatcher”, what do you see?

You could be forgiven if your first thought is Kevin McCarthy or Donald Sutherland, each running away from crowds of invading, shapeshifting aliens. But for many those two words evoke the earliest days of Hollywood Horror. The opening of the beloved 1931 classic ‘Frankenstein’ was, and remains, iconic – two figures, neck deep in grave dirt, hoisting an enormous, mud-caked coffin out of the ground, all while the figure of death looms behind them. Dramatic, vivid (and a little impractical).

(Frankenstein, 1931)

Meanwhile, Mary Shelley writes in her classic 1818 novel that her protagonist was “forced to spend days and nights in vaults and charnel houses”, and that to him “a churchyard … was merely the receptacle of bodies deprived of life, which, from being the seat of beauty and strength, had become food for the worm”.

A grimy, haunting description, depicting the living lingering where the dead lie sleeping. But, more than that, this chapter in Victor Frankenstein’s search for the secret to life spoke of a much more familiar trade in death – one that Mrs Shelley, and the country she called home, knew all to well.

But why? What could possibly justify disturbing the dead in their final resting place, and how did this dismal trade go about it’s work? Like Mary’s immortal gothic tale, this is a story of science pushing the limits of morality, ranging from the righteous pursuit of medical enlightenment to the practicalities of cold, hard cash. As notes changed hands and cadavers were heaved over churchyard walls, the art of body snatching reveals a fascinating underbelly that stalked the streets of Georgian Britain while it slept.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The key to this story lies not in the churchyards, but on the doctor’s slab. Medical science had long understood that to cure the body, you needed to understand how it worked. That meant getting up close and personal with as many fresh corpses as possible, armed with a scalpel and a strong stomach.

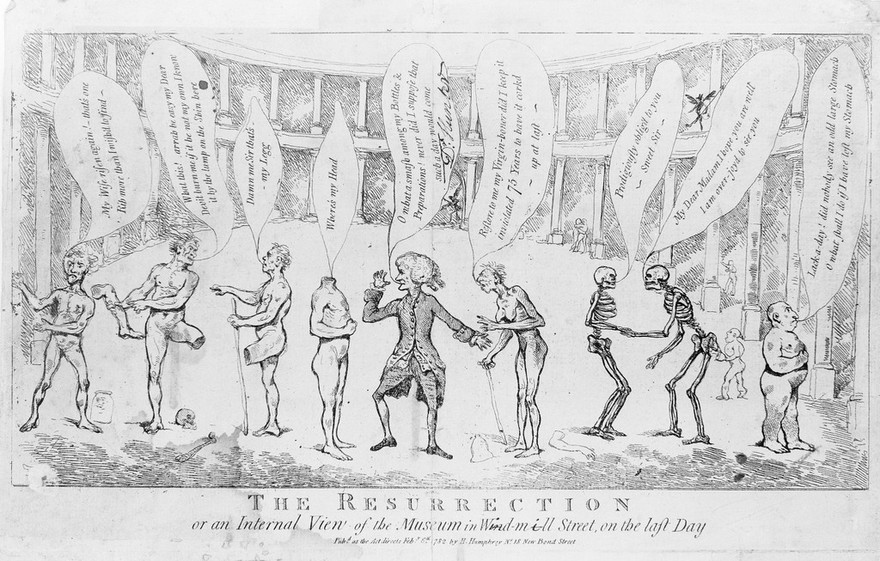

But doctors were hamstrung by religious and social stigma. Christian funeral rites in the 19th century relied on the care of the body, something that most believed you would need, intact and ‘unmutilated’, after death. The act of dissection was a violation of the “eternal peace” envisioned when the dead were laid to rest in churchyards, awaiting in hope of ‘resurrection’. This was also the basis for a lot of early resistance to cremation.

There were attempts to find exceptions to these religious and social norms. In Scotland, James IV granted certain executed criminals to the Edinburgh Guild of Barbers and Surgeons in 1506, and in England Henry VIII gave the Company of Barbers and Surgeons access to four hanged men in 1540. By 1752, the government allowed judges to sentence any convicted murderer to both execution and public dissection, where bodies were opened by expert surgeons in front of an eager public and hundreds of avid students. These corpses were an ‘acceptable’ target for the doctor’s curiosity; dissection was both a scientific tool and a punishment, feared perhaps even more than the noose itself.

However, the small stream of criminal cadavers were nowhere near enough to meet the growing demands of the numerous teaching hospitals and anatomy schools popping up across the country, especially in its capital cities. This only worsened as beliefs about the study of anatomy evolved. Spearheaded by the famous Hunter Brothers, many late 18th-century doctors agreed that students needed to dissect the body themselves. What was the odd demonstration at the back of some overcrowded theatre compared to finding and feeling the intricacies of the human body with your own hands?

Some schools promised a whopping two cadavers per student, a competitive offer in the “market” for medical qualification as young doctors scrambled to stay on top of the rapidly evolving discipline. But where would they get the reliable flow of cadavers necessary for their innovative curriculum? They were hardly likely to have volunteers.

(Wellcome Collection)

As William Hunter famously wrote, dissection was a “necessary kind of inhumanity” – the future of surgery and the key to saving countless lives. Students needed bodies, bodies the government refused to provide. For the Doctors, matters had to be taken into their own hands.

This is why, in the early days, most body snatchers were the anatomists themselves. One of our most in-depth sources on the whole ‘grave trade’ comes from the memoirs of Sir Robert Christison, Scottish physician and President of the British Medical Association (1875), who recounts his youth in Edinburgh in the early nineteenth century.

(Wellcome Collection)

Christison recounts stories of the anatomists’ assistants and aspiring doctors he knew in his youth who braved the churchyards at night (though Ruth Richardson speculates Christison may have been an accomplice himself as a young student). Often led in small groups by their teachers, the young men collected their own ‘subjects’ to study in class the next day. His memoir recounts many tales of close calls as the went about their dark business, and, as we’ll see, the tools of the trade.

However, as time went on, the public became savvy about what went on while they slept. Disturbed graves and snatchers caught in the act put many, particularly those in university towns, on high alert. Not only was the art of grave robbing getting tricky, but doctors also wanted to distance themselves from what most in Britain agreed to be an offence to “Christian Morals”.

Enter the Resurrection Men. Generally, these were people already embroiled in the business of the dead – hospital porters, gravediggers and sextons, though anyone in want of a little cash could find themselves with a spade in hand. Some worked alone, especially in the early days, but most formed tight-knit and often terrifying gangs with strict territories in the cities they called home. Not only that, these gangs built up expansive networks of informants. From offering intel on the freshest bodies to providing a quick getaway, even just keeping quiet if they saw anything untoward, a cut of the fees went a long way in allowing the body snatchers to get on with their work.

Tragically, our sources on these groups are woefully limited. The best accounts are the testimonies given at the Select Committee Report on Anatomy in 1828, designed to end the practice of body snatching once and for all. The report includes statements on the gruesome trade from both doctors and a few anonymous body snatchers, understood to be members of the notorious London Borough Gang.

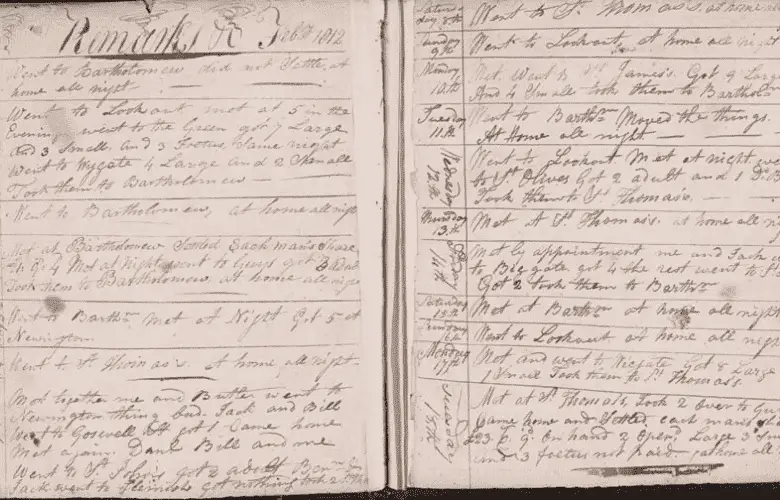

We also have the infamous Diary of a Resurrectionist – a fragmented collection of notes generally attributed to Borough Gang member Joseph Naples, documenting their dealings between 1810-1812. Republished and edited by the Victorian historian James Black Bailey, the diary offers a tantalising insight into their nightly dealings- everything from money exchanged, the numbers of bodies collected and even rivalries with other local resurrectionists.

(Hunterian Museum)

Between these sources, as well as Christison and some scattered newspaper articles covering other snatchers caught in the act, we can paint a startlingly practical picture of how exactly you went about stealing a dead body.

Timing was the key. Most anatomy schools weren’t open all year round, generally starting in October and finishing sometime in May. In the days before refrigeration, the colder months leant themselves to keeping the bodies fresh on the doctor’s tables, and for the ones tasked with exhuming them, darkness was essential. Generally, they chose the early winter evening, around six to eight o’clock – too early for the night watchmen but dark enough to avoid detection. Gangs even kept track of the moon, with Naples’ diary including charts to keep track of the monthly phases and marking days where it was “too bright” to go out.

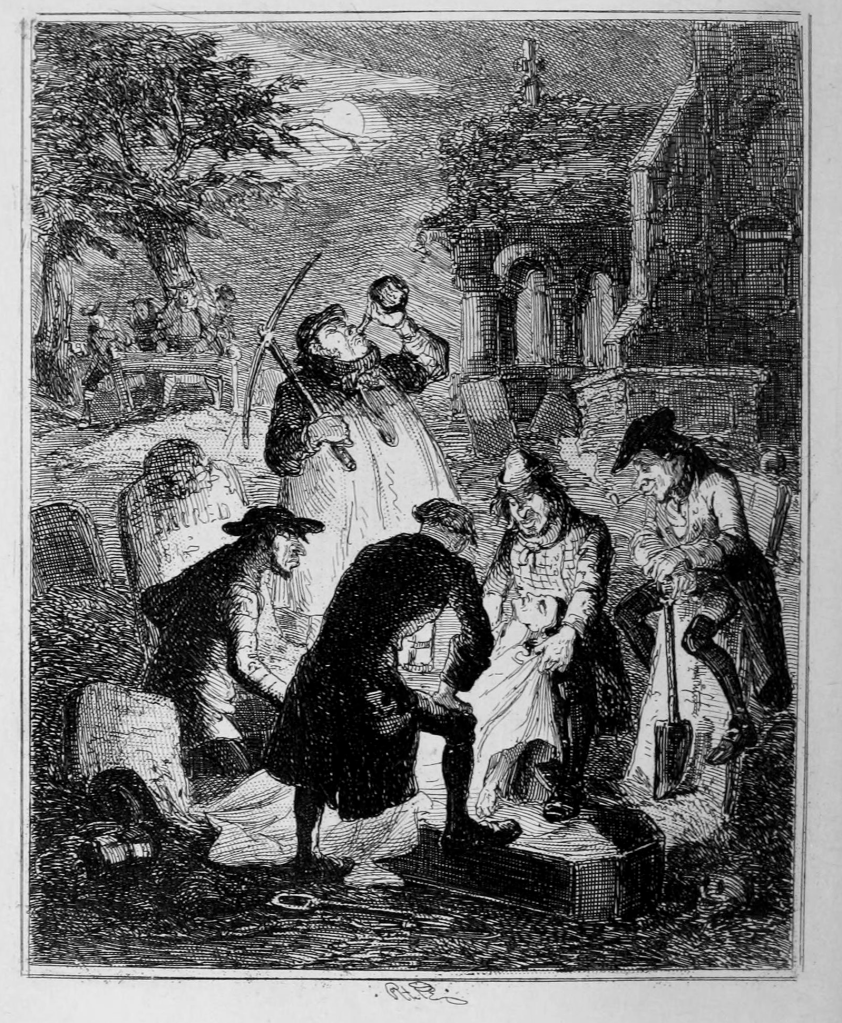

With the sun beneath the horizon, the gangs made their way into the churchyards, either hoisting over the walls or striding through the conveniently unlocked gates (likely secured with a cut of the earnings to the local sexton). It was time to get to work.

With a few stationed as lookouts, a sheet would be laid on the ground beside the fresh grave. This protected the grass from any stray earth that might be left behind the next morning. Digging just at the “head” end, they would reach the coffin quickly (usually the earth was still soft from where the grave had been dug a few hours before). Using the rest of the dirt still settled on the coffin for leverage, hooks would be lowered under the lid to break open the wooden lid. Body snatchers would often pad the top with sacking to muffle the sound.

Once the opening was big enough, the task was as simple as hoisting the body out of the grave and stuffing it into a nearby sack. The soil was piled back into the hole and a waiting carriage would whisk the gang to the doctors, waiting ready with the fee. According to Christison, all of this could be done in under an hour – perfect for multiple scores in one night.

Of course, this was not the only way the “Resurrection men” could claim their cash. For example, before he joined the Borough Gang, our diarist Joseph Naples was the gravedigger for Spa Field Grounds. Taking advantage of his position, news reports tell us that Naples would carefully remove bodies from the coffins during the day, backfilling the grave to raise the corpse just a few inches from the surface. Covering them with a thin layer of soil to avoid suspicion, he would return later with baskets specially provided by local hospitals, removing the bodies under cover of night with little to no sound or effort.

Perhaps each body snatcher had their own technique – again, the scarcity of accounts outside London, Glasgow and Edinburgh means we can’t be sure of every way the gangs went about their business. We do have news reports, like those covering Naples’ first arrest, that leave little clues from robbers caught red-handed – stories of wooden shovels to mask the sounds and special “dark lanthorn” lanterns that only cast small amounts of light. It seems that swiftness and subtlety were the keys – any way that a body could be removed quickly and quietly was no doubt tried and tested.

Many even cut out a trip to the graveyard altogether. There are scattered accounts of snatchers paying women to impersonate grieving relatives and collect the unclaimed dead from Britain’s workhouses, taking advantage of the state’s reluctance to pay for a pauper’s grave. Meanwhile, others bribed servants and undertakers to take a body just before the coffin was closed while it lay out in a family’s house. Both of these were difficult, especially since the opportunity for the latter would be very limited and would need the coffin to be weighted convincingly to avoid detection. But if pulled off correctly, and with money exchanged in the right places, the corpse would be even fresher than those dug out of the ground.

But the graveyard was the preferred target, and even with all the right tools and carefully placed payments, plenty could still go wrong.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, the biggest fear was getting caught, but this wasn’t for the reasons you might expect.

The law itself left a large loop hole – to this day you cannot legally “own” a corpse, so when the gangs went to get the body, more than happy to haggle over it with the doctors like meat at a market, they technically weren’t stealing anything at all. If caught with a corpse, the most you could be charged with was offending public decency – a misdemeanour that would get you a few months in prison at the most. However, if found with anything else – from grave clothes and jewellery to even pieces of the coffin itself – that was a different matter. Any of these could put you down as a thief, which promised a much harsher sentence. Most body snatchers were careful to strip the body once it was out of the ground, throwing anything they found back in the hole and taking the cadaver as naked as the day it was born.

Bribery went a long way, but there are plenty of stories where resurrection men were chased out of the yard with dogs and pistols. One of the problems with targeting more isolated communities, particularly as urban areas became more vigilant, was that there were more opportunities to get found out on the way home. Though some stories tell almost “Weekend-at-Bernies”-style tales of dressing bodies up as sick or inebriated friends to get past the authorities, all it took was one nosy watchman or toll-keeper to give the game away.

Beyond the authorities, inter-gang rivalries could spell disaster. Each group guarded their territories fiercely, and at the Select Committee several stories emerged where one gang either informed on the other or even left graves deliberately open to raise alarm. Fights could break out when Anatomists bought bodies from other sources, with some evidence that gangs would retaliate by raiding the hospitals and destroying the offending corpse beyond use. It was a brutal business that squabbled over a scarce resource – there was no room for sharing.

(Wikipedia)

Then, of course, there were the bodies themselves. All it took was bad information or even just a warm spell; after all that effort to dig the hole and prise off the lid, many body snatchers were forced to abandon their prize where it lay. Sometimes the body was riddled with diseases like smallpox, but more commonly it had decayed beyond its use. If their goods weren’t fresh then gangs had no choice but to cover the earth back up and go home empty handed, though many supplemented their income by selling “extremities”. If arms, legs or even a head were still in good condition they could be removed and sold as teaching examples, and many used pliers to remove teeth for the rising denture trade.

By the early 19th century, most of the communities surrounding anatomy schools and teaching hospitals were well aware of the gangs and their business. Horrified that their families might be taken in the night, they only made the resurrection men’s jobs more difficult.

At first, families simply left out tests to see if a grave had been disturbed – placing subtle markers like stones, leaves and shells to check if they had been moved overnight. But when body snatcher’s quickly caught on to the trick, carefully replacing the token back where they found it long after the grave had been emptied, the families upped their game. Some employed servants or night watchmen to stand guard over the grave, while others patented ingenious contraptions, such as iron cages known as “mortsafes”, to stand over the body until it had decayed beyond use – accessible only by lock and key. One famous and memorable gadget was the “coffin gun”, remotely triggered to shoot any assailant that came after the body resting peacefully below the grass.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, most of these tricks and traps were only affordable to the “upper crust”. Generally, body snatchers targeted the poorest areas, going after burial grounds packed close to the surface, brimming with bodies and with the promise of several fresh ‘subjects’ in one night’s work. Very rarely would the gangs feel the need to go after the more upmarket burial grounds guarded by such intricate contraptions.

Besides, even if Doctors wanted someone specific, perhaps someone with an ‘unusual’ body or specific cause of death, most felt confident that they could get them for the right price. Sir Astley Cooper, president of the Royal College of Surgeons, gave testimony to the Select Committee that “there is no person, let his situation in life be what it may, whom, if I were disposed to dissect, I could not obtain”. All of these dangers only allowed the gangs to raise their fees.

And a tidy sum they were too. Though it is difficult to pin down the exact ‘going rate’ paid across the country, Ruth Richardson estimates that a fresh adult cadaver could fetch you as much as £4 4s, whereas any corpse delivered under three feet, usually called a “small” or a “foetus”, was paid for by the inch. Many doctors testified that the amounts had doubled several times over in all their years of procuring bodies for their students.

Although the money was quickly spread among the gang and their webs of accomplices, compared to the average earnings of any other “skilled” tradesman they could amount to a very comfortable living indeed. Certainly enough to make disturbing the dead worth your while.

But inevitably the age of the Body snatcher had to come to an end. The heights of public outrage reached their peak in Edinburgh in 1828, when the infamous Burke and Hare chose to ‘cut out the middle man’, as it were – committing an increasingly bold series of murders to furnish the dissection tables of Dr Robert Knox.

(Wikimedia Commons)

This was closely followed by a similar string of crimes down south – this time a more traditional gang of body snatchers known as the “Bethnal Green” gang, who turned from grave robbing to murder in 1831. It seems all the worse fears about the dismal trade came true. Why spend time digging in the wormy earth when a much fresher prize lingered in the poorest corners of Britain’s cities?

The Select Committee published its report a few months before Burke and Hare took their last victim, and this series of crimes helped set its findings in stone. The committee concluded that the present state of the law was “injurious” to the pursuit of modern medical science, arguing that new provisions must be made to provide a steady stream of “subjects” by the state.

This culminated in the Anatomy Act of 1832, which gave all the country’s unclaimed dead, generally found in hospitals and work houses, to the Anatomists. For many, this was just a different kind of injustice – once again it was the poor who were most at risk from the doctor’s the scalpel, while the rest the country’s well-to-do could sleep soundly in their graves, undisturbed. But, in one swoop, the corpse trade was neutered beyond recovery – the final nail in the coffin.

Of course, the art of exhumation was not extinguished overnight, and the fear of the Resurrection Men lasted well into Queen Victoria’s reign. But with the surgeon’s theatres filled with a new source of corpses to carve, the days of hefting over graveyard walls and smashing coffin lids came to an end. The resurrection men found new ways to earn their trade, many in the very hospitals they stocked for so many years, and the dead, at least those laid to rest beneath the earth, remained undisturbed.

By Minette Butler – Curator

If you have any inquiries about our museum – please email us at nfm@tcribb.co.uk.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Bailey, J B, The Diary of a Resurrectionist 1811-1812, (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1896), in Project Gutenberg, <https://www.gutenberg.org/files/32614/32614-h/32614-h.htm> [accessed 9 January 2023].

Christison, R, The Life of Sir Robert Christison, Bart.(Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1885), in Google Books, <https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Life_of_Sir_Robert_Christison_Bart/Mj1YxwEACAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0> [accessed 9 January 2023].

Select Committee on Anatomy, Report from the Select Committee on Anatomy.(Great Britain: House of Commons, 1828), in Wellcome Collection, <https://wellcomecollection.org/works/hyjrxujv/items> [accessed 9 January 2023].

Secondary Sources

Durey, MJ, ‘Bodysnatchers and Benthamites: The Implications of the Dead Body Bill for the London Schools of Anatomy, 1820-42’, The London Journal, 2.2, (2013), 200-225.

Laquer, T, ‘Bodies, Death and Pauper Funerals’, Representations, Feb.1, (1983), 109-131.

Lennox, S, My Macabre Roadtrip (2023) <https://mymacabreroadtrip.com/> [accessed 9 January 2023].

Richardson, R, Death, Dissection and the Destitute (Suffolk: Penguin, 1988).

Ross, I & Ross, C, ‘Body Snatching in Nineteenth Century Britain: From Exhumation to Murder’, British Journal of Law and Society, 6.1, (1979), 108-118.