Black horses pulling black, glass sided hearses, topped with ostrich plumes and draped in dark velvet, the funeral trade boasted a wide array of ‘grim’ trappings for hire. However, not all of these curious traditions live on into the 21st century – be it in popular culture or modern funeral furnishing.

Here at the National Funeral Museum, we are lucky to hold a collection of a so-called “Funerary Hatchments”. All three are diamond shaped panels , measuring between 50-60 cm across, and are painted on wood or silk. They depict various ‘nonsense’ coats of arms, each with the word “FUNERALS” proudly emblazoned below.

(Source: National Funeral Museum)

These signs were hired by clients to hang over their front doors – announcing to the street that there had been a death in the household. Hatchments could be found displayed in undertaker’s shop windows well into the mid-20th century, but nowadays they are a rare and curious find, even in the trade.

So, where did they come from?

Like a lot of British funeral culture, hatchments can be traced back to the grand funerals organised by the College of Arms. A division of the Royal Household, they still exist today as the “heraldic authority” for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and much of the Commonwealth. They mostly oversee the recording and granting of new coats of arms, as well as taking part in ceremonies like Coronations and the State Opening of Parliament.

However, back in the day the ‘Heralds’ also acted as something like a State funeral furnisher – organising and conducting the elaborate obsequies of the country’s most elite. These were reserved only for those possessing titles and coats of arms, including Knights and Bishops, Counts and Dukes, all the way up to the Monarchs themselves.

The “heraldic funeral” was a masterclass of colourful pomp and splendour, designed to symbolically represent the inalienable authority of the landed and titled to rule. Attended in person by the College’s senior ranks (the so-called “Kings at Arms” and their attendants), these funerals centred around an elaborate, theatrical procession. People from all ranks were invited to participate, with the parade led by the community’s poorest and progressing up to the local officers and guilds. This progressed all the way to the the ‘chief mourner’, usually the deceased’s heir, who walked directly behind the coffin and was followed by the deceased’s other family, friends and neighbours.

Aside from the body, the real stars of the show were the ‘achievements’. These were a collection of specially painted banners, escutcheons and armour made just for the funeral, designed to represent the deceased’s crests and coats of arms. Carried just ahead of the coffin by the herald’s attendants, these colourful and elaborate pieces included helms and crests, spurs and gauntlets, tabards and swords; impressive representations of the deceased person’s titles and rank.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

During the service these ‘achievements’ would be ceremonially offered to the chief mourner before being displayed somewhere in the church as a kind of memorial. You may even come across some surviving helms or tabards in old churches today.

Every funeral was ordered and furnished according to the deceased’s rank; the more ‘penons’, ‘standards’ and ‘guidons’ in the procession, the higher their status in life. The College kept a strict eye on etiquette, setting rules on how many and what type of each achievement befitted your status. Meanwhile, they reserved the right to prosecute anyone caught overstepping – either from armigerous families asking for more elaborate furnishings or even from non titled families commissioning or using ‘fake’ achievements (more on that to come).

These ceremonies were meant to reinforce not only the family’s wealth, implied in the costly accessories and mourning clothes, but their inherent authority as the country’s nobility. By managing the scale and contents of each funeral according your prescribed rank, the College kept tight control on the strict hierarchies at work within mediaeval and early modern society.

So, that’s a heraldic funeral – but where does the Hatchment come in?

Though commissioned from the official herald painters, hatchments weren’t actually considered ‘official’ achievements, though some sources suggest they were carried in the procession all the same. Hatchments would depict the deceased’s individual coat of arms on a large, diamond shaped panel and they even came with their own code. At a glance, those in the know could tell the deceased’s gender and marital status – even if they had left a spouse behind or had married more than once.

(1) A Man with a surviving Wife (2) A Woman with a surviving Husband (3) A Widower who married again, leaving a surviving Wife

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

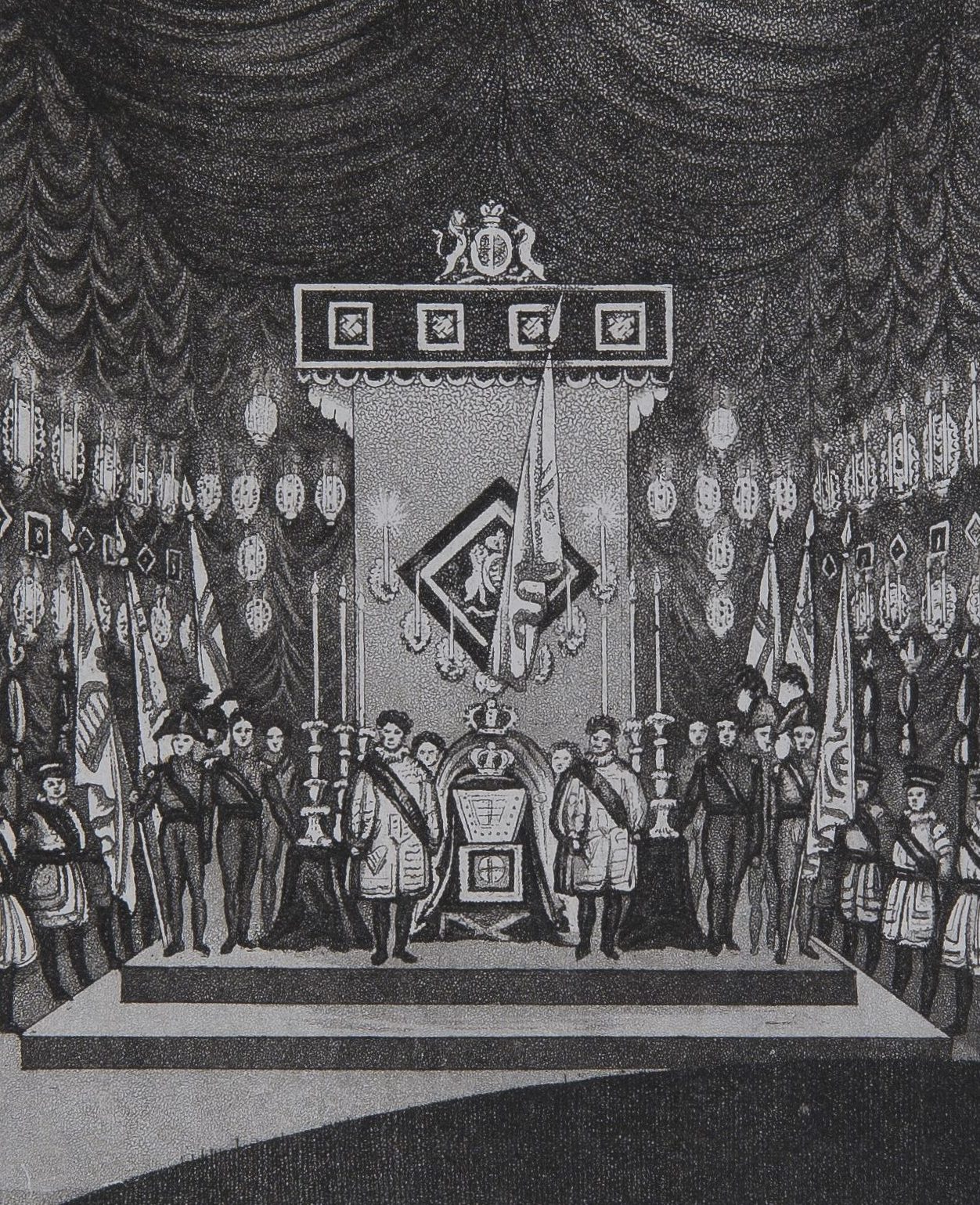

They would be displayed on the front of the family home to announce the death, but they’d also be hung over or around the coffined body as it ‘lay in state’. You can find hatchments in the background of many famous funerals well into the 19th century – such as Nelson, Wellington and the various deaths of British royalty. Accompanied with black fabric hangings and torchlight, they made an impressive and solemn sight.

Like the achievements, hatchments would eventually be transferred to the church. Since most burials in family vaults wouldn’t usually have individual monuments, hatchments acted as a personal memorial and are sometimes our only clue that a body had been buried in the family vault at all.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

But these aren’t quite the hatchments we have here at the museum. How did this exclusive and jealously guarded symbol of the landed elite become a common sight on many an ‘ordinary’ street in Victorian towns and cities?

This ties back to the history of the College of Arms. Though still around today, the institution lost much of its power and influence in the late 1600s, particularly as a funeral furnisher – mainly by pricing themselves out of a rapidly developing ‘market’.

A heraldic funeral was always an expensive affair. Though only the entitled elite were allowed the honour, even they could not expect the College’s work for free. In fact, the heralds set fees by your rank – for example, in 1618 their services cost £2 for a gentleman or £10 for a knight, all the way up to £45 for a duke, duchess or archbishop. This didn’t even include the hiring of a pall or the fees for the herald painters who actually made the achievements, let alone other non-heraldic expenses like mourning clothes and the post funeral ‘feast’ offered to the attending poor. As you can imagine, even for the wealthiest noble families, these costs could stack up quickly.

When they were the only ones able to provide such a lavish array, the heralds could quite happily enjoy all their tidy fees. However, this all began to change when a new trade entered the scene.

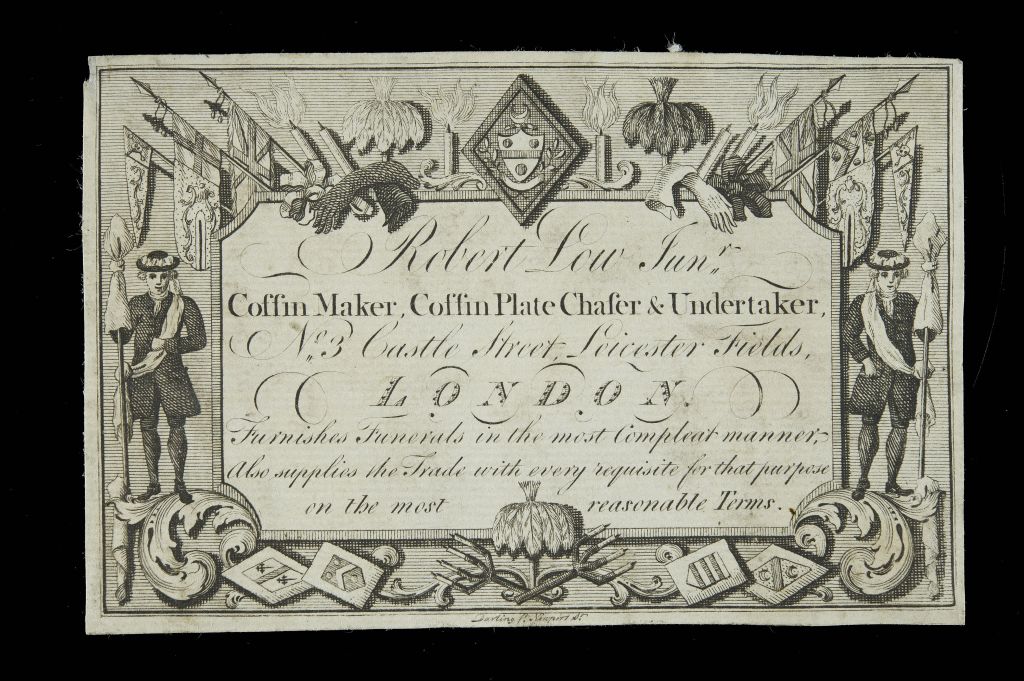

These were the Undertakers – a collection of carpenters, sign painters and other businesses who took up the task of furnishing funerals on the side. They made their name not only by supplying coffins or palls – something trade guilds and local craftsmen had been doing for many years, but by offering funerals to rival heraldic pomp and splendour.

(Source: John Johnson Collection, Bodliean Library)

Of course, in the early days the College would have, and did, come down on these imitators like a ton of bricks – zealously guarding their exclusive rights to paint coats of arms and to furnish aristocratic funerals.

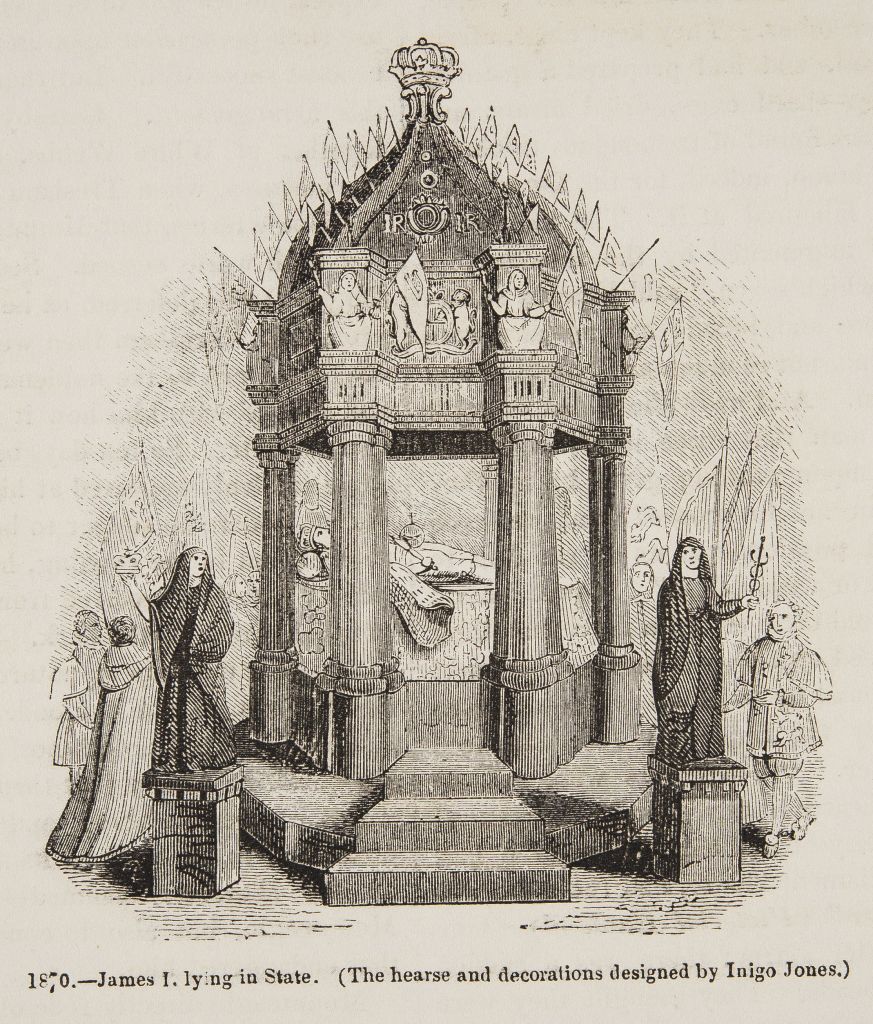

But on top of the hefty prices, several incidents had injured their reputation among their elite clientele. Celebrated funeral historian Julian Litten points to the practice of “droits” at royal funerals, where along with their fees and generous gift of black fabric from the Great Wardrobe, Heralds were caught whisking away other furnishings used during the service, like chairs and tables, to divide amongst themselves – most famously at the funeral of James I in 1625.

On top of being generally seen as underhand, this incident particularly caused tension with Westminster Abbey, who felt that since these items were left on their premises, conveniently on display to a paying public, then they should belong to them. The argument was not a great look for the expensive College and Litten notes that after 1625 many noble families started going straight to the herald painters to furnish their funerals, rather than deal with the jealous and bickering institution they worked for.

(Source: ILN from National Funeral Museum)

Though the College survived the Civil War, notably furnishing a spectacular and distinctly ‘Royal’ funeral for Oliver Cromwell, the heralds saw a significant drop in their profits after the Restoration. Fashions were changing, as the rich began to prefer more private, night time processions, and the heralds found themselves losing out on their wealthiest and previously exclusive clients.

The College did their best to chase after increasingly popular imitators, notably signing a deal with the Painter’s Company in 1686 to stop their members making ‘fake’ achievements, as well as successfully prosecuting two painters for painting and marshalling a funeral 1687, but this wasn’t enough. Undertakers were popping up all over the country’s towns and cities and it turned out traditional prestige meant little against a quicker service and lower, more transparent prices.

In 1689, the Undertaker William Russell actually struck a deal with the College to get their members to attend his client’s services, lending them an air of authenticity that benefitted him much more than the heralds (though it’s unclear if they ever actually followed through on the agreement). By 1699, they were barely doing a handful of ceremonies a year and, as Litten says, their attempts to legally challenge their imitators failed dismally.

The College finally lost Royal favour in 1717, when a disagreement over the christening of Prince William saw the Lord Chamberlain, head of the Royal Household, taking charge of what counted as a “public” occasion worthy of the Herald’s services. Hiring its first Undertaker, William Harcourt, for the funeral of Frederick, Prince of Wales, in 1751, it was clear the College were beaten. Though the Heralds still contribute to “State Funerals” even to this day, they had lost out to the ambitious, growing trade.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/OWTU6EMOIO5QPMDGCJSFTGGJSY.jpg)

(Source: The National News)

But none of this actually explains the Hatchments. This is because while the rise and fall of the elites laid many of the funeral trade’s foundations, the Undertaker’s real money was found in the up and coming middle classes. These were a rising group of merchants, traders and other business owners who were eager to emulate or even outdo the traditions and fashions of the old guard, despite having no titles or coats of arms of their own.

With money to spend, these families wanted the grand processions full of pomp, ceremony and elaborate accessories, and this encouraged undertakers to think outside the box. ‘Achievements’ like plumed helmets could be replaced with trays of ostrich feathers, dyed black to reflect the solemn occasion. Meanwhile, accessories like the herald’s long white staffs of office were replaced with black “wands”, and even other mediaeval traditions like castle guards at the gate became the sour face mutes – professional mourners to lead the procession and stand outside front doors, armed with staffs of black crape. All familiar tools found in the background of many a Dickens novel or other TV adaptations, the trade’s links to the red bricked College are draped over its enduring, iconic image.

(Source: National Funeral Museum)

Which brings us back to our hatchments. As said before, these weren’t actually considered “official” achievements, meaning they were some of the easiest heraldic accessories to copy. Undertakers could hire official herald painters to make them with little to no trouble, as long as they were subtle and exclusively made for armigerous families.

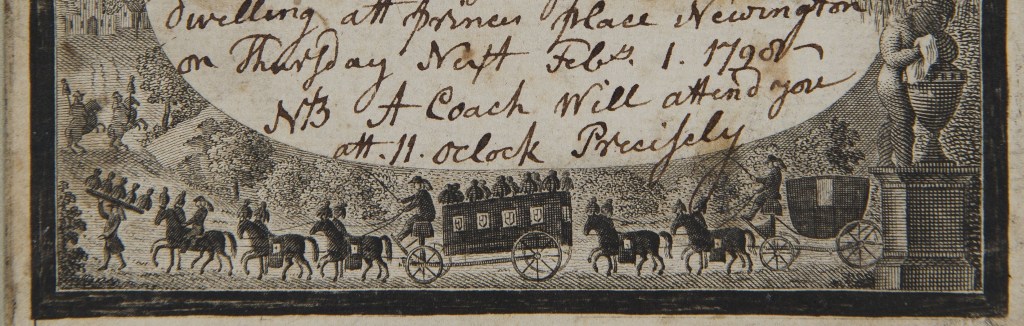

When the College lost its legal crusade, Undertakers became bolder and bolder. They commissioned their own bogus hatchments for their rising middle-class clients to use, with early trade cards depicting them right alongside other typical funeral pomp, such as torches, mourning gloves and ostrich plumes.

(Source: National Funeral Museum)

The diamond shaped panels would be hired out on request, painted with ‘general’ coats of arms and maybe with mottos reading “funerals” or other suitably grim phrases. By the age of Queen Victoria, even the poorer working classes could, in theory, enjoy the trappings once reserved for the country’s most ‘noble’ members – for the right price, of course.

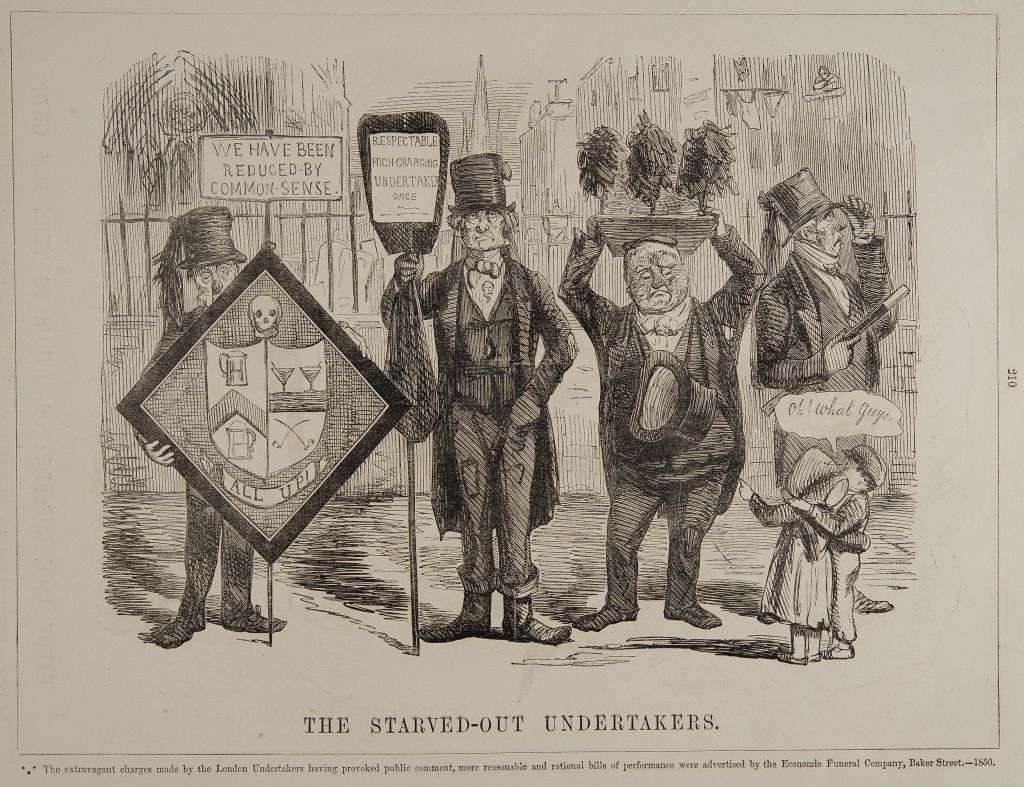

Hatchments had become so recognisable that they were easy fodder for satire and ridicule; this print below depicts one painted with beer mugs, criticising the trade for its unflattering reputation for drunkenness, ‘upselling’ and performing grief for hire.

Punch Magazine approx. c. 1850

(Source: Punch Magazine from National Funeral Museum)

Like many of the elaborate accessories of Victorian funeral furnishing, the Hatchment fell out of use in the early 20th century. This was probably due at least in part to the First World War, when in the face of such widespread death elaborate processions and long mourning periods were seen as in ‘poor taste’. Many of the men who would furnish and perform the funerals sent away to fight and the Black “Friesian” or Belgian horses, traditionally used for funerals, were cut off from Britain by the western front.

The trade had to adapt and although the exact cause is unclear, it’s likely the Hatchment was one of many ‘luxuries’ that were slowly left behind even after peace was declared in 1918. The horse drawn carriages became the motor hearse, the mutes and the ostrich plumes an elaborate movie prop – but it seems the beautifully painted panels had no ‘modern’ role to assume in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

(Source: National Funeral Museum)

Of course, the Hatchment didn’t disappear overnight. In fact, T Cribb & Sons still had paintings like these hanging in their windows well into the 1950s and 60s, though by then they’d become little more than decorative relics and were rarely used. Many modern Funeral Directors still have these signs hidden away in their shops – mostly no longer on display, they are a curious reminder of the trade’s often unconventional history.

By Minette Butler – Curator

If you’d like to see our hatchments in person or have any inquiries about our museum – please email us at nfm@tcribb.co.uk.

Bibliography

Day, JFR , The Heraldic Funeral (2000) <https://www.theheraldrysociety.com/articles/the-heraldic-funeral/> [accessed 10 March 2023].

Litten, J, The English Way of Death: The Common Funeral Since 1450 (London: Hale, 1991).

Litten, J, ‘The Heraldic Funeral’, The Coat of Arms, 1.209, (2005), 47-68.